The Scientist and The Sacred | Boiling River Research Plumbs Remarkable Depths

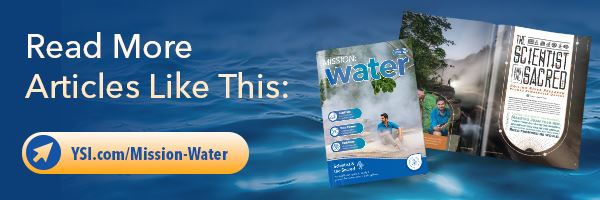

Andrés Ruzo made a vow to the shaman. Maestro (Teacher) Juan Flores, an Asháninka healer, gave the young scientist permission to study the waters of Peru’s mysterious Boiling River. The locals call it Shanay-timpishka, “boiled with the heat of the sun.” Ruzo wanted to understand the geologic processes and mechanisms that give rise to the steaming river—how hot it was and where the water came from. That would require him to collect and export samples of the sacred river’s water.

“After you study the waters,” Maestro Juan told him, “Pour them onto the ground, wherever you are in the world, so the waters can find their way back home.” Ruzo promised he would.

Researcher Andrés Ruzo shares images and videos of his scientific data along the Boiling River with Maestro Juan Flores, an Asháninka healer. Photo Credits: Steve Winter

Researcher Andrés Ruzo shares images and videos of his scientific data along the Boiling River with Maestro Juan Flores, an Asháninka healer. Photo Credits: Steve Winter

Legend of a Tropical Hell

As a boy, Ruzo heard the legend of the Boiling River from his grandfather. It was part of an elaborate torture the defeated Incas brought upon gold-lusting conquistadors. Want gold? There’s a whole city of it in the Amazon: Paititi, El Dorado, the City of Gold. Go there. Quench your thirst.

Survivors staggered back with stories of a tropical hell: eternal night in the dark of the rainforest, its shadowy depths guarded by silent warriors with poison-tipped arrows, spiders big enough to devour birds, clouds of insects, and a river that could boil a man alive.

As a young Ph.D. candidate at Southern Methodist University (SMU) studying geothermal science, Ruzo (@georuzo) let his grandfather’s tale bubble back to the surface of his mind. A map of thermal springs in Peru made him wonder if a boiling river could actually exist in the Amazon forest.

Not likely, said the scientists. Of course not, said the prospectors. I’ve been there, said his aunt.

In fact, his aunt showed him the way to the steamy banks. Ruzo wrote a book about their journey to the Boiling River, an expedition funded by a National Geographic Explorer grant. He gave a TED Talk that has logged more than 2.4 million views, and he has been interviewed for countless articles and television broadcasts about his scientific discovery of a river where the members of the local Amazonian tribes have held sacred for generations. The forest around the river was still patrolled by bird-eating spiders and native shamans, as well as wasps, mosquitoes, lumber traffickers, and illegal squatters. But the forest was shrinking.

Photo Credits: TED (Duncan Davidson)

Photo Credits: TED (Duncan Davidson)

In his interviews, speeches, and books, Ruzo's language carries great drama, the sense of awe that comes with seeing through the vapor in the forest and realizing that the dream is real.

More than that, his writing crackles with urgency. He has watched clearcuts and burned stumps spread like a malignancy across the landscape around the Boiling River. He has been racing against the chainsaws and torches that threaten its ecosystem and the river itself.

“Imagine being in this beautiful, cool, twilight world of the forest and suddenly opening up and stepping out into a totally deforested, apocalyptic landscape with massive tree trunks as big as your car—trees that you knew,” he says, describing a trip back to the Boiling River through newly cleared land. “You go to the greatest celebration of life on the planet, and you see it go silent.”

After that harrowing trip, Ruzo put his dissertation research on the back burner and dedicated himself to telling the story of the Boiling River to the wider public. He used science to make the case for protecting the area around the Boiling River and became an advocate for land rights for the people who ancestrally call this jungle home.

After that harrowing trip, Ruzo put his dissertation research on the back burner and dedicated himself to telling the story of the Boiling River to the wider public. He used science to make the case for protecting the area around the Boiling River and became an advocate for land rights for the people who ancestrally call this jungle home.

“There is a moral obligation to science,” Ruzo says.

“I learned to be a scientist from Western thought—that’s how I was trained,” he explains. “But my seeds of conservation working in the Amazon came from Maestro Antonio Muñoz, a Shipibo leader. He opened my eyes and said, ‘You’re here. You’re documenting everything. Is that enough for you? Is just documenting the destruction enough?’"

Before he published the science for fellow researchers, Ruzo promised himself he would help protect the landscape. He spent years raising awareness of the river and its magic, and helped indigenous leaders obtain the legal rights to their land. Now that the land belongs to the indigenous residents, Ruzo has turned back to publishing his data.

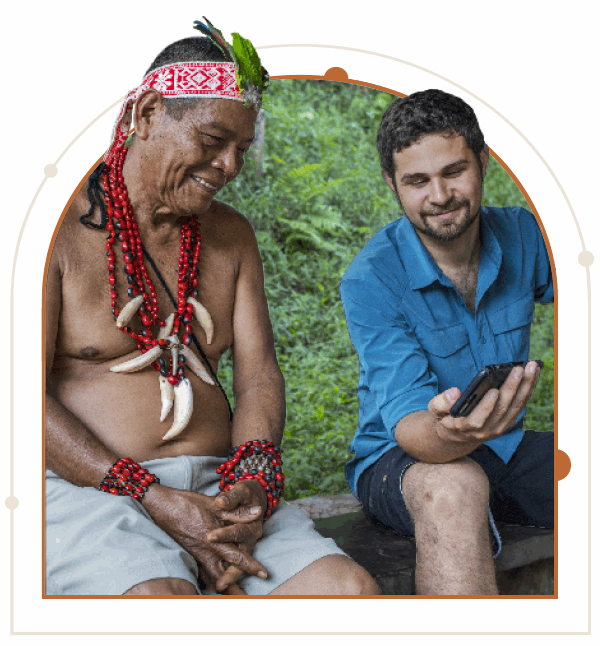

Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

Science and Story

The locals say Shanay-timpishka—the Boiling River—is the home of Yacumama, Mother of the Waters, a giant serpent spirit who gives birth to cold and hot waters.

The Boiling River starts as a cold, small stream that runs about 3 kilometers (almost 2 miles) before hot water is injected into it.

Its first thermal pool is found beneath a large boulder that resembles the head of a giant serpent—the Yacumama—protecting the pool beneath her motherly, protective jaws. The indigenous residents say the steam of the Boiling River carries the prayers of the jungle up to the heavens.

Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

Ruzo first heard the lore of the river from Maestro Juan as the two walked along its banks. To map out the river's temperatures, Ruzo took thermal readings every 10 meters (32.8 feet). The forest was too dense for a clear GPS signal, so he started with a known GPS control site and used a 10-meter length of rope carried by members of his travel party to measure temperature along the river's flow—a distance of over four miles.

"I literally tied my cousin to a high school friend of mine, and we went 10 meters by 10 meters by 10 meters down the river," Ruzo explains. (Building on that original work, Ruzo has used drone-based thermography to take his readings.)

As they worked their way down the river, they stopped at La Bomba, an aggressively bubbling hot spring, whose name translates to “the Pump”, where Ruzo measured the river's temperature at 94 to 97 ºC (201 to 207 ºF). About 300 meters (1,000 feet) downstream of La Bomba, the river's water temperature peaked at a spring reaching 99.1 ºC (210 ºF).

Photo Credits: Sofia Ruzo

For over 6 kilometers (about 4 miles), the river wove through rocks, dense jungle, and thermal mudflats, widening to a peak of about 30 meters (100 feet) and hitting a maximum depth of almost 4.5 meters (15 feet).

Along the way, temperatures ranged from the ambient air temperatures of around 27 ºC (80 ºF) to steaming stretches bubbling at average temperatures around 90 ºC (194 ºF). Major stretches of the thermal portion of the river far exceed 47 ºC (116 ºF), the temperature where falling in becomes life-threatening.

The Boiling River is more than the confluence of hot and cold water. It’s also not just a scientific curiosity for Ruzo, an accomplished student who grew up in Peru, Nicaragua, and the U.S. It's the junction of modern science and traditional knowledge, the kind of age-old observations that find their voice in legends. Ruzo learned to respect them both.

“My biggest single surprise from working at the Boiling River was realizing that every significant geothermal site on the river that we mapped and measured with modern Western Science had already been identified as culturally significant places with the most spiritual power,” he explains.

"Though the final interpretations of what we see are different, both knowledge systems are observing the same energy from the Earth. There are these points of interest along the Boiling River because the heat flux is higher at these specific points. It's where you've got major geothermal water intrusion coming up into these fault-fed hot springs. Each one of those had spiritual significance. Every single one. And there were stories and myths and legends associated with all of them."

Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

Work of Powerful Spirits

One of the deepest mysteries remains the source of the hot water. The Asháninka believed Shanay-timpishka was the work of powerful spirits, which made perfect sense, Ruzo notes. After all, it is remarkably safe to drink, unlike most other local water sources that often plague drinkers with dysentery, Legionnaires' disease, and other diseases.

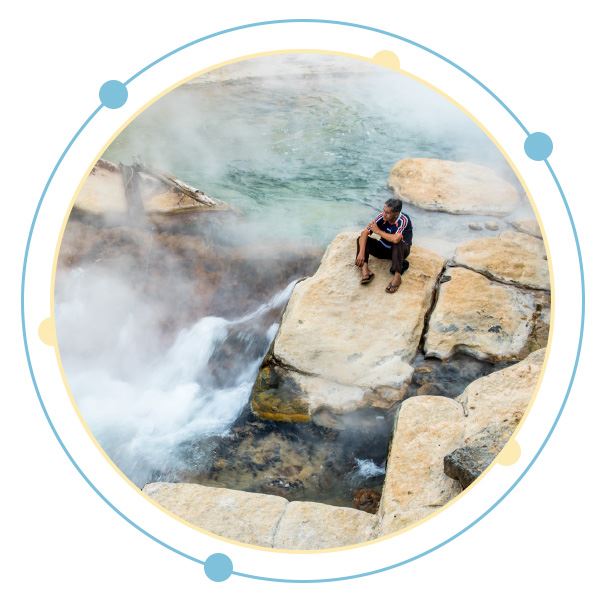

The safety of the water—its heat and its purity—were the heart of its mystery not only to the locals, but to Ruzo. He uses a YSI Pro Series handheld meter to test the pH, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP, or redox), and electrical conductivity for clues on the river’s path deep into the earth and back. He also uses the instrument to characterize the waters from different inflow points along the river and monitor changes over time.

"I've worked on geothermal systems all over the world, and you wouldn’t want to drink most of these waters," Ruzo says. "They can be full of heavy metals, be highly acidic or alkaline, or even harbor things like 'brain-eating amoebas.' The first time I did an elemental analysis of the Boiling River’s waters, I also ran waters from a volcanic system in the same set. The results for the volcanic system were crazy—everything was in that water, it was just off the charts. In the case of the Boiling River, there was effectively nothing in the water, to the point that we did not have enough readings to do the targeted tracer studies.”

“It was humorously frustrating: the waters were stupidly clean.”

"Using my YSI, I found the Boiling River’s waters were 'cleaner'—i.e., lower electrical conductivity—than Evian. How’s that for a scientific observation?" he laughs. "Now, let's take that to a cultural and humanistic standpoint. You could understand why the indigenous people would say, 'This is the work of powerful spirits because it's healthy water. This was put here to heal us.'"

Along the Ring of Fire, the volcanic rim that circles the Pacific Ocean, hot springs are usually charged by active volcanic processes. Their waters carry not only the heat of melted crust, but also minerals and gases that can spike the electrical conductivity and mineral readings Ruzo mentioned. But the Boiling River doesn't bear that mark of magma.

The river sits in the middle of the Peruvian Volcanic Gap, a volcanic "blank spot" nearly 1,400 kilometers (860 miles) long in the Ring of Fire where the actively subducting Nazca Plate does not produce active volcanoes. The exact reason for this remains a geologic mystery and subject of serious debate, but is thought to be linked to flat-slab subduction geometry, Ruzo notes. As a result, the Boiling River is 700 kilometers (430 miles) from the nearest active volcano.

So the Boiling River wasn't a typical volcanic hot spring. However, Ruzo still had to ensure that it was not a gushing oil drilling mishap, especially because it is less than two kilometers north of the oldest actively producing oilfield in the Amazon Basin. Oilfield accidents like the Lusi mud volcano in Indonesia provide shocking reminders of what can happen when an oil well is overpowered by a geothermal system, Ruzo points out—there, steaming flows of hot mud displaced thousands of people in East Java.

Photo Credits: Sofía Ruzo

The ancient legends in the Amazon implied that the river had been boiling for untold generations, but Ruzo needed to confirm it. It took Ruzo about a year to get access to old oilfield reports buried deep in the archives at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Written in the early 1930s by a geologist named Robert B. Moran and his colleagues, the proprietary reports make it clear that the exploratory party had encountered the Boiling River and found it "disturbing."

Magmas can overheat buried oil, rendering it worthless, so the last thing a prospective investor in a new oil venture wanted to hear was that the deposits were near a volcanic hot zone.

Moran and his colleagues reported on the existence of the hot river near their proposed oilfield site, but noted that it did not tie to volcanism, the thermal waters were not volcanic, and the river was not a concern. In fact, they attributed the Boiling River to “mass pyrite oxidation” in the subsurface heating the waters.

Deep Dive

Residual heat from the creation of Earth, coupled with radioactive decay, make the deep reaches of the Earth's crust extremely hot. In most parts of the world, says Ruzo, geothermal scientists figure on temperature increases of about 25 ºC (77 ºF) per kilometer of depth.

Based on the purity of the water, geochemical and geophysical data, geologic models, and his confidence that it is not spurting up through a broken well, Ruzo believes the Boiling River is fed by water that dives deep into the Earth, gets heated by the surrounding rock, and is propelled by heat and pressure back through faults to the surface.

Still a mystery is why the water of the Boiling River is quite so clean. Ruzo explains that it is still a matter of great debate in the geothermal community, and he hopes new data from his expeditions will help better constrain the problem. Currently, there are three leading hypotheses in the literature, he says.

It could be that the system is so ancient that the rocks along the water's underground path have reached a chemical equilibrium with the flowing waters. Alternatively, it could be that over time, the waters deposited minerals along these subsurface flow paths that now minimize rock/water interactions. Or perhaps the Earth is acting as a giant retort vessel, boiling the water in a subsurface lower-pressure zone and resulting in a distillation process that blows off pure steam that condenses closer to the surface.

Ruzo hopes further research—including an investigation of chlorides in water from the Boiling River and improved geothermometry and age-dating work—will shed light on the path of Shanay-Timpishka's waters.

Even as he works to explain the mysteries, Ruzo celebrates the sacredness, the magic, of the Boiling River.

"My 5-year old son asked me the other day, 'Dad, does magic exist?'" Ruzo says. "And all I could say was, 'Absolutely, because we live on this planet where you can go to the poles and see the auroras dancing or sperm whales shooting super-powerful blasts of concentrated sound that might stun or even kill a giant squid—or experience the magic of the Amazon's biodiversity with an explosion of life, colors, and shape, and where, literally, rivers boil and legends seem to come to life.'"

Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

Keeping His Promise

Ruzo has introduced the Boiling River to an estimated 800 million people around the world through his website, boilingriver.org, and countless articles, videos, and awareness campaigns. Shanay-timpishka and the land around it remain in the “reddest” of Peru’s deforestation red-zones. However, Maestro Juan Flores and his community now legally own their land, the river is now listed as a conservation priority for Peruvian conservation groups, and it is also at the center of an active conservation campaign calling for the government to formally protect the site.

Over the past decade, Ruzo has brought geologists, microbiologists, ethnologists, and many others to the Boiling River. And every expedition includes Peruvian and international researchers and young scientists. Many will be co-authors of research that Ruzo is finally publishing along with the dissertation he is completing under Dr. Andrew Quicksall at SMU. Ruzo says he will honor Maestro Juan Flores as a co-author, as none of the work would have been possible without his traditional knowledge and mentorship.

In the meantime, Ruzo has plans to collect more data and more samples. And he continues to keep his promise to the Shaman.

As promised, after the water samples are fully analyzed, Ruzo dutifully pours them out onto the ground so they can find their way back home.

"I will go to a nice spot and just think about the river, the jungle, and all the people that have helped me get to where I am," he says, “It has become an act of gratitude—tinged with the scientific curiosity of wondering how long it will take for the waters to make it back. That's what goes through my mind as I pour out the waters."

Additional Information

Additional Information

Ruzo’s Tools

In his trips to the Boiling River in Peru's Amazon rainforest, Southern Methodist University (SMU) Ph.D. candidate Andrés Ruzo depends on many sophisticated instruments to study the science behind the river's steaming waters: thermal imaging cameras, custom-built thermo-resistor tools, drones, specialty lights, and a handheld meter from YSI, a Xylem company.

Ruzo was introduced to YSI's handheld meters in an SMU class by renowned water quality researcher Dr. Andrew Quicksall and quickly realized how important one would be for his own studies.

"Dr. Quicksall's class showed me how the pH, electrical conductivity, redox potential, and other parameters all come together to help understand what kind of environment that water is in," Ruzo explains. "It made the invisible visible in a way I thought was really powerful."

"Dr. Quicksall's class showed me how the pH, electrical conductivity, redox potential, and other parameters all come together to help understand what kind of environment that water is in," Ruzo explains. "It made the invisible visible in a way I thought was really powerful."

"Understanding the Boiling River’s waters is important for far more than just the geoscience," he adds. "I have colleagues from the University of Miami studying ecology, colleagues from the University of Michigan looking at microbes, and others from the Agrarian University of La Molina in Lima, Peru, studying mushrooms. We're all looking at this system from slightly different angles. How do you connect those dots? You connect them with chemistry.

"I see chemistry as the musical notes that allow me to get to one of nature's soundtracks," he adds. "Otherwise, how are you going to quantify the invisible?" That's no small feat in the rainforest far upriver of the nearest frontier town, where the dangerously hot river currents and the tropical, humid environment present a major challenge for equipment. Ruzo has seen the rugged conditions take their toll on cameras and a wide range of scientific tools, and the Boiling River's hottest reaches require him to let his water samples cool before measuring them.

Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

But he also knows he can count on his hardy YSI Pro Series handheld meter to give him the insights he needs to quantify otherwise-invisible chemical parameters that give him a glimpse into the geologic processes at play at the Boiling River.

“What I love about my YSI instrument is that it is tough and dependable,” Ruzo says. “It can take all the beating of day hikes in less-than-ideal conditions and yield results I can count on.”

Opening the Door to Science

Andrés Ruzo is doing more with his Ph.D. studies on Peru’s Boiling River than exploring the geothermal phenomena behind the streaming water. He’s opening doors for a wide range of fellow scientists. Since first visiting the Boiling River in the Amazonian rainforest in 2011, Ruzo has organized 15 expeditions to its banks and collaborated with more than 50 investigators who brought their expertise in ecology, entomology, various aspects of Ruzo’s specialty of geoscience, botany, microbiology—even linguistics.

For Ruzo, it is essential that every field of the team is diverse and multi- or cross-disciplinary. His field teams are always a mix of local Peruvian and international collaborators, scientists, media people, educators, students, and a host of other volunteers.

“For me, this is a battle for the future of our jungle, and everyone has something unique to offer the cause,” he says. “Furthermore, as a Peruvian scientist, I poignantly feel the negative legacy that exploitive ‘parachute’ or ‘drive-by’ science has left behind. For this reason, a major focus of each field season is capacity building and catalyzing collaborations between locals and foreigners. This is a community effort, and we all have a role to play.”

Since 2016, every expedition has also included at least one high-school-age participant.

“So much of human history was written by the actions of young people, and this goes beyond the often cited cases of, ‘Alexander the Great conquered the known world at 27,’ or ‘Albert Einstein claims to have hit his peak in his mid-20s,’” Ruzo says. “Whether it was fighting in wars, working the farm, or running the factory, kids 16 years and younger regularly contributed in so many ‘real world’ ways.

Andrés helps his wife, Sofía, cross a jungle stream. Photo Credits: Delvin Gandy

“For me, getting high schoolers involved in science and working on real problems is a key to building a better tomorrow, and should be a part of everything we do,” he says. “These kids don’t deserve to be babied. If I find a student who wants a path forward to work and make a positive impact, I want to make sure I open that path for them to run—to gallop.”